No Second Chance READ CHAPTERS 1-3

Chapter One "Guilty"

The jury filed into the courtroom.

I knew the verdict and I was ready. I had said goodbye to the two friends who’d sat through the three-day trial – and I’d warned them they’d be leaving without me. For the first time in two decades, I knew where I was going.

I stood to face the judge.

“Guilty on the following offences: entering premises with the intent to commit indictable offence; assault occasioning harm … yadda …”

Their fantasy – so far removed from my reality.

It was a daytime soap opera, and I was expected to play my role: like Lindy Chamberlain, I remained poker-faced and tried not to think of what the newspaper had written about me that day.

If you ever have to stand trial in a court of law, I highly recommend the Maryborough courthouse. The tranquil lawn and gardens overlooking the river can make all the waiting around feel like a day in the park. You can hide in the magnificent cave-like root system of a giant fig tree. An intoxicating aroma of freshly brewed coffee – from the bigwigs’ café – lingers in the air, adding a sense of charming normality to a dark episode of your life.

The Maryborough courthouse is the oldest and longest serving courthouse in Queensland, but I can’t pretend it was good to be back. This was a retrial.

I first stood trial here in 1998. Thanks to a legal technicality, a re-trial was scheduled, but I missed it. I went to ground, went bush. It was now 2016. I was back and the wheels of a somewhat twisted justice were grinding on.

My ugly accuser and his straggly blonde girlfriend with the nicotine fingernails sat with the prosecution team, while the sweet-faced media waited breathlessly, grasping their handfuls of stones, eager to throw first.

Stone the shrew! Hang the witch! Lock her up!

I was being prosecuted by my stalker. For two years he sexually harassed, threatened, and savagely assaulted me. When he went after my kids, I stood up to him … and the coward ran to the police. The irony of it: the abuser becomes the abused – and it worked for him.

His physical strength and his hair had diminished with age, but his hatred had grown into a permanent dark and menacing scowl.

His Honour, Justice Smith, sentenced me to two and a half years’ imprisonment on each charge, to be served concurrently. This five-year sentence was to be suspended for the duration of three years after I had served ten months in prison.

In considering my sentence, His Honour decried my lack of remorse and my absence from court in 1999, requiring a warrant to be issued for my arrest.

His Honour also took a few positives into account: “Your success in raising your four children,” he said. “Your actions, while at large, were admirable. And the fact that this case is now twenty years on, and you have no criminal history, suggests that this was not your normal behaviour; it is unlikely that you will reoffend in the future.”

Justice Smith was a kindly man and I respected him, but, in an instant, we had moved beyond ‘Innocent until proven guilty’ – I was now the prisoner in the dock.

That glass dock was built for women like me – women who fight back. Yet, while it caused me to consciously withdraw from reality, it was more like a nursery crib to the seasoned women I was about to meet.

I was on my way to a high security prison.

—

It was like a heavy metal pub brawl at Maroochydore watch-house, my second watchhouse in three days. Locked up at the end of a tunnel of cement cells, I was assaulted by every sound that hit my wall: the radio blaring in reception; the police forever talking to one another or on the phone; the crazy woman screeching; another woman crying; and a bloke who’d watched too much American TV shouting for the fifth amendment.

My hands shook as I tore off toilet paper to jam into my ears. I pressed the palms of my hands hard against the side of my head. We were issued one grey blanket. I’d used it to cover the thin, filthy, green vinyl mattress. Whipping it up, I wrapped my head in it, to no avail.

Spreading the blanket back over the filthy mattress, I sat crossed-legged, pulled the hood of my coat over my head, and observed my breath. But my mind rejected equanimity; I was too far gone. The grand finale to twenty years of living on the edge, and the horror of what lay ahead, met in that endless noise.

A prison cell doesn’t offer any means of escape, but a glimmer of hope came with the odour of a hot sausage roll that had been delivered as lunch. I could use it to bargain with: “Hey, you! You can have my sausage roll if you shut up!” I called out to the fifth-amendment guy.

We could not see one another, nor did I know how I would get the sausage roll to him, but he didn’t want it anyway.

“Don’t tell me to shut up. Shove your sausage roll up your back-ring, fuck you …”

The crazy woman laughed and hooted from somewhere at the other end of the passageway. I imagined her in a red hoop skirt, swirling around and around and around.

I should at least be grateful that I wasn’t locked up with one of these loud-mouthed loonies. Penned alone, I didn’t have to talk, or watch my back, or share the stinking toilet.

I no longer knew if it was day or night, as there were no windows, and sunlight never reached the end of the corridor. As the days passed, and the uneaten food piled up on the bed, I began to panic. I needed air. I had to get out of this place.

I pressed the red emergency buzzer and to my surprise a voice responded immediately.

“Get that hood off your head,” boomed the voice in the wall. “I can’t see who you are!”

Who did he think was in my cell?

I heard footsteps coming along the passageway. The jangle of keys outside my cell had me knocking the hood off my head. The hood was attached to my army green coat. The coat was all I had to keep me safe. It smelt like home.

I had bought that coat for ten bucks. It had been reduced from forty-nine. Casually stylish, it could be worn anywhere: to the shop, to dinner, to a presentation – even to jail. I used to wear it bushwalking or when I walked the dogs. I wore it to town, with everything shoved in the big pockets: phone, purse, pen, car keys, and reading glasses. If it rained, I put the hood up. It wasn’t raining in my cell, but the hood had kept the electric light from giving me a migraine. It protected my face from the spit-n-blood-n-snot vinyl mattress.

The door swung open. A walrus entered my cell. His moustache twitched as he looked me up and down. “Hand over the coat, prisoner.”

“No, please let me keep the coat,” I said, hugging it to me like a strait jacket.

“Take the coat off!” The walrus shouted. “Why are you still wearing civilian clothes? Show me the zip in those pants.”

I looked down at the metal teeth in my grey trousers – was he implying I had a weapon in my cell?

“Prisoner, take off the coat!”

I peeled the last layer of my life from my body.

The walrus took my coat and my trousers. He left me standing in my bamboo underpants and the blouse I’d worn to court. When the cops at the Maryborough watch-house had cut the neck strings off the blouse, I was dumbfounded, because a Barbie doll could not have hung herself with those strings! They’d taken my shoes as well, but they let me keep my coat. I found a dollar in the pocket and handed it to a female police officer the next day. She was extremely grateful, and I then realised that even a coin left on a prisoner could get them into trouble.

Alone again, I sat down on the narrow slab of a bed and stared at the stained stainless-steel toilet bowl. There was no lid. The water within was dark and murky. I looked at the cold sausage roll, the pastry sunken into the meat.

In time, the walrus returned with a pair of size 20 tracksuit pants. I’m size ten. I had to bunch the waist band to prevent them falling around my ankles every time I stood up. The well-worn material, stiff with washing powder, was harsh against my prison-virgin skin.

Some hours later, another policeman appeared at my cell door. “Do you want to take a shower, prisoner?”

I shook my head. It was the first shower I had been offered, but I had no inclination to stand naked in this place.

And then one day, a friendly constable opened my cell door and handed me back my grey trousers – zip and all! “Put them on,” he said.

He returned a few minutes later. “Hold out your wrists.” He snapped a pair of handcuffs on me. “Follow me,” he said, and I was led out into the sunlight.

My bare feet padded over the warm concrete. I raised my face to the sun and was grateful to breath the fresh air. Looking around, I was acutely aware of how different the world looked from a prisoner’s point of view.

A policeman unlocked and opened the back door on a police truck. Behind that door were two smaller padlocked doors. I could hear the other prisoners inside, yelling back and forth, from one pod to the other.

The policeman unlocked the left-hand pod and told me to get in. Handcuffed, it wasn’t easy. There was one other person inside this pod. She sat with her back against the adjoining wall, yelling to the prisoners in the other pod. I knew from her voice that it was the crazy woman – she wasn’t wearing a hoop skirt, but rather, a green prison-issue tracksuit.

The door slammed shut behind me and the bolt locked into place. I quickly slipped past the woman and sat with my back pressed safely up against the cabin.

Chapter Two Annie Oakley

She didn’t look anything like I’d imagined. She was late thirties and boldly attractive with long, straight brown hair. She had washed-out, slightly blemished skin, but you didn’t notice that unless you looked closely – and I was sitting close enough to notice. It was the laughter lines at the side of her eyes that held my attention.

If this woman wasn’t crazy, she had to be brave, or have an outlandish sense of humour, because who else would disrespect the authorities the way she had, back at the watchhouse?

As the vehicle rocked into motion, she fell silent, as did our fellow inmates in the next pod. We drove a few short blocks before speeding off down the highway. There was a small, barred window directly in front of the woman, and, even from my position, pressed against the cabin, I could see the Sunshine Coast flashing by. Nostalgia hit me, and I guessed she was feeling it too, because suddenly her handcuffs fell between her knees and she leaned forward, resting her head on the bars.

“The Killing Fields!” she whispered.

What on earth did she mean? Now, she was quiet, I wished she’d talk.

As if reading my mind, she turned to face me. “No-one knows where I am. I went out and just never got home again. I’ve been in lock-up for two fucken weeks. And not one fucken phone call! It’s fucken illegal!”

She said she was worried about her son and ranted about her interfering mother. She didn’t really see me, and, if I spoke, she only waited to continue speaking. This self-focussed attitude was something I would soon take for granted, slowly begin to understand, and learn to appreciate in prison.

I didn’t interrupt her. “The bastards arrested me while I was out on the town, off my tits,” she said, eyeing my grey trousers for a length of time – which gave me a sense of existing after all. “Mate, they didn’t give me my fucken clothes to put back on! You were lucky. I’ll tell you why I wasn’t. I was wearing a red fucken mini-skirt, a yellow boob-tube and long green socks when they nicked me.”

“Oh,” I said, shivering, “I wish they’d given me back my coat.”

She didn’t respond. She didn’t seem to notice the cold air blasting in, or that our pod was like a meat freezer, or that her ears were turning blue. I searched the interior for any way to communicate with the drivers.

“Can we contact them?”

“Fuck no. They don’t give a shit about us,” she said earnestly, “We’re at the mercy of our captors. Get used to it!”

How many people had made this crowded lonely journey to prison? Sitting there, seemingly calm, my innards were in turmoil – such grief, and anxiety, and helplessness.

“I got these wrists from trail bike riding!” she said, suddenly, holding up her strong, shackled wrists, dragging my mind from my own thoughts to her Wild West attitude, and in that moment, I re-named her Annie Oakley.

We all find our own method of coping. I guessed Annie Oakley used bravado. I went undercover. As a teenager I’d read a book titled The Snake Pit, in which a journalist has a nervous breakdown and is committed to a mental institution. She copes by believing she is on an assignment. Whilst basking in my watchhouse cell, I had decided this was how I was going to cope with being in jail. Annie Oakley would be my first assignment. Of course, interviews had to be disguised as polite conversation, but in chatting with her, I learned she’d been in prison before. I didn’t know what for, because that’s a question you never ask – but she did tell me she dreaded going back to that prison hellhole.

—

Brisbane Women’s Correctional Centre is located on Grindle Road at Wacol. It’s a high security prison – a mass of cement buildings surrounded by high wire fences and topped with coiled razor wire. It took over two hours to get there, making only one stop to drop Sausage Roll Amendment off at the men’s prison.

The police truck reversed into an area outside the prison walls, beep, beep, beeping. I sighed with relief – which is just weird when you’re about to be imprisoned!

Oddly, I already felt something akin to a sisterhood with Annie Oakley. It wasn’t because of our situation, and it wasn’t because I was the type to join sisterhoods. I would have liked her no matter where I met her; I just hadn’t quite fathomed what I liked about her… yet.

The pod door opened. Sunlight streamed in with the constable’s face. “Well, out you get, then,” he said, moving aside to open the second pod.

We jumped out to stand in the triangular space between the back of the vehicle, the back entrance of the building, and a high wire fence. A small bird flew down from the blue September sky and landed on the coiled barb wire. It was the size of a mouse. It looked straight at me, waved its little tail, and flew off.

That bird, oh that bird!

A moment later a plump girl jumped down from the second pod to stand with us. She barely looked sixteen. I’d never had so much as a speeding ticket in my life. I was not a drunk, or a junkie, and had never smuggled recipes interstate – yet here I was.

“Wrists up,” said the police driver, and he quickly removed our handcuffs.

“March inside, prisoners!”

Barefooted, we walked between the two policemen, down a corridor, one side of which was a wall of thick glass. A Māori girl stood behind the wall of glass, watching.

The corridor led into a reception area where we were told to sit down in a row of plastic chairs that faced the front desk. The police drivers and the prison officers chatted like people who met up every day, and maybe they did.

Some minutes later, three more prisoners were escorted into the reception area. A brawny woman with a crew cut, tattooed neck and no teeth; a petite but busty woman in her early fifties; and a wild-haired larrikin. As there were only three chairs they were told to stand in the doorway. In time, all six of us were called to the desk to be processed.

A very pleasant Aboriginal officer dealt with me. She said, “I’ll put Aboriginal descent for you,” and went ahead and wrote it down before I could correct her. This mistake would find me at an Aboriginal smoke ceremony a few weeks later.

“You can sit back down now, prisoner.”

Processed, we were led back along the corridor and locked up behind the thick glass wall, with the Māori girl.

I lay down on a bench against the back wall and rested my head on my arms, alert to the goings on. The hefty, toothless woman with the tats looked as miserable as hell on a Sunday. She sat on the end of the bench, near the half wall that hid the toilet, and kept her eyes downcast, grunting occasionally.

The plump girl who’d travelled in the truck with us looked at the Māori girl and said, “Hi, I’m Nina, what’s your name?”

“Macy.”

“I’m Zorba,” said the petite, busty woman, and then told us her life story in one rushed sentence. It went something like this: “I was a wealthy businesswoman until things went tits-up and left me with no option but to strip for a living, and that’s how I ended up here.”

Meanwhile, Annie Oakley had taken to the wild-haired larrikin like a possum up a tree. The pair swaggered about, looking each other up and down like two old cobbers who hadn’t seen one another since the war, and then they started telling tales.

No sooner had Annie Oakley finished telling of her mini-skirt arrest than Spinner took over. She told how she’d robbed an establishment in the city. Running out front, she knew the cops had been called, so she jumped a hedge. “I ran faster than a speeding train to the wrecker’s yard, scaled the fence and shit me-self. There was a couple of watch-dogs waiting for my arse!”

Tats Grunter snorted and went to sit on the loo behind the half wall.

“I dropped off that fence, right, and took off running – and up ahead I see this lady standing beside a four-wheel-drive. She’s scratching in her handbag with the driver’s door wide open! Well, hell, darling, there was my ride. I was behind the wheel before she looked up … but wait for it.”

We were all waiting.

“I was on my way, a free bird, right, and how easy was it? But then I hear a baby crying. I checked the radio. Nope. So, I look in the rear-view mirror, right, and there is this toddler strapped into a car seat in the back-fucking-seat. I swear to God…”

“Oh no! So, what’d you do?” said Zorba.

“What could I do. I drove back. Cops were waiting for me.”

I think this was my first inkling of what lay beneath the seemingly rough and brazen façade of some of my fellow inmates. I sat up and really looked at Spinner. She was thirty-something, short, with wild brown hair and a face that warned you not to mess with her. A lowlife might have abandoned the car, baby and all, and escaped, but she drove back … right into the arms of the cops.

“Mate,” said Annie Oakley, who’d been eagerly awaiting her turn. “I mooned the security camera at the Brisbane Airport then pissed off in a stolen rental car. I was off my tits, right?” she said, mimicking her new friend’s manner of speech. “I get up the road, right, and I see these two hitch-hikers with their thumbs out. What the fuck. Jump in! They’re, like, international, from fucken England and, I tell you what, mate, those kids got a fucken doozy Australian story to tell the folks back in Pommy land.”

Tats Grunter grunted from the toilet.

Nina giggled.

Macy, still standing by the wall of glass, smiled.

I wished I had a pen and paper.

Old stripper, Zorba, was up and pacing, but we were all listening!

“The cops were soon on my arse, sirens blaring. It was on. High speed chase. Me hitchhikers were having the time of their life, screaming in the back seat, waving their arms around like tourists.”

I almost laughed out loud for the first time in a week.

“They didn’t catch us. Bastards nicked me a couple of days later. I just spent almost two fucken weeks in the watch-house. Not one phone call. That’s fucken illegal!”

The pair of car thieves got louder with every yarn. They jumped around each other like sparring roosters. Zorba cut in with her tit-shaking, dollar-grabbing stories but Annie Oakley and Spinner were only interested in out-doing each other – not her.

As the pitch in the holding cell reached a crescendo, a stern-looking female guard burst in and told us to shut up or else.

“Or else, what? You’ll lock us up?!” sniggered Spinner.

Ignoring her, the officer turned to me. “You! Come with me.”

Chapter Three Strip Search

I followed the prison officer back into the reception area. Two more heavy-duty female officers were waiting. Both wore boots and heavy belts, hung with bats, leather pockets and walkie talkie.

“Behind the curtain, prisoner,” said one of the officers, handing me a paper bag and pointing to a curtained area.

Behind the curtain was a small space with one straight-backed chair. I put the paper bag on the chair. The shorter guard stepped into the small enclosure with me. The other stood holding the edge of the curtain, watching. I was told to remove my clothes one item at a time.

I pulled my blouse over my head. I don’t wear a bra and felt their eyes upon my naked breasts. It worked for me to pretend I didn’t care. It’s just a shift in consciousness. A change of attitude. I’d had twenty years to practice things like this. I imagined they were thinking She’ll have no chance of keeping up that suntan in prison.

Where there is a will, there is a way, even behind bars.

“Shake your shirt,” said the short guard. “Then drop it in the bag.”

I unzipped my pants. One must adapt quickly in prison. I whipped my trousers off, shook them, and tossed them into the bag with my blouse. Stepping out of my knickers, I wondered why I was being strip searched. I had not been convicted of any drug offence.

In any other circumstance, the scenario behind that curtain would have been obscene! Two big women, fully clothed and armed, ordering a small woman to get naked, against her will, while they watched. But we were just getting started. Before I could drop my knickers into the bag, the officer holding the bag said, “Do you need a separate bag for your pants?”

I guessed she was asking if my knickers were dirty.

“Nope,” I said, tossing them in.

I was stark naked. Stripped down to nothing left to hide. It should have ended there but the taller guard stepped into the space and said, “Bend forward and toss your hair over your shoulders.”

Were they searching for nits?

This was just the beginning of the indignity women must endure. How traumatic for those who had suffered violent relationships or had been raped or tortured – and there are many such women in prison.

“Open your mouth.”

“Poke out your tongue.”

“Stretch your lips.”

“Turn around and face the wall.”

“Lift your right foot.”

“Lift your left foot.”

For me, the issue was not about being naked – it was being ordered to get naked. It was the stage-show scenario. The belittling of another human being. I’d just met a woman who gets naked for a living, but I knew this was not going to be easy for her.

“Pick up the paper bag,” one officer said, pointing to the paper bag on the straight-backed chair. She handed me a towel and opened a door within the curtained area.

“Step inside, prisoner.”

I entered a tiny cement space. There was no window to climb out, not a drain to slither down, not a fire escape, just a shower nozzle and two grubby taps.

Inside the bag was a cake of yellow soap, a cheap toothbrush and toothpaste.

Showering for the first time in days, I tried not to think about the germs crawling under my feet or to notice the dried blood and spit on the damp walls. Done, I dried myself on the towel that Brer Rabbit had dragged through the briar patch and then given to Brer Fox – to piss on.

As a hygiene freak, I’d already braced myself for this filth.

Back behind the stripper’s curtain a pile of clothes had been placed on the chair: a faded boob-tube, a new pair of high-waisted, elastic underpants, and a blue tracksuit, the material worn and stiff from washing powder. The ‘Correctional Centre’ logo was printed on the right leg. The term ‘correctional centre’ irked me. I’d rather have ‘prisoner’ as my logo. It would allow me to own my ‘crime’. Some crimes are not to be ashamed of, and, as far as I was concerned, my behaviour did not need correcting. I live in a society that allows the abuse of women and children – that’s what needs correcting.

While the other prisoners were stripped and showered, Nina and I sat on a chair in the reception area, eating breakfast cereal. Well, Nina ate both our packets of Rice Bubbles while I stared at my initials on two white sacks. These sacks were stacked on a portable wire cage. Two of them had M.F boldly printed on the side. Oddly, seeing my initials, made me feel present in that moment. They had been expecting me. The strange disassociation from my surroundings faded, as I stared as those sacks. While I was locked in a cell and riding in the meat wagon, people were waiting for me, writing my initials on bags. This was real.

I stared at those sacks, my breath caught in my throat, and I blinked back tears. I felt so desperately hopeless, but right then something bloody funny happened. Annie Oakley shot out from behind the curtain with her long brown hair dripping wet and said, “A fucken cup of tea would be lovely,” – and, out of nowhere, a genie appeared, bearing plastic cups of tea on a plastic tray.

The genie was a small woman with short brown hair and a kind face. I guessed her to be late sixties. She was wearing a blue prison-issue uniform, just like us. A prisoner serving prisoners tea! And the tea was hot, it was sweet, it was white, and it tasted like … oh, my God, it was just so good. It was an unexpected delight to have a hot, sweet cup of tea.

A few minutes later, this kind genie was back carrying socks and sneakers. She squatted down at my knee and asked, “What size are you, love?” Dell really did have the kindest voice. I would never have guessed that she was doing sixteen years for murdering her husband. Every new prisoner is fortunate to meet this woman. Her gentle voice soothes the fear and eases the transition, because her kindness gives you hope that there might be other friendly women behind bars.

Once each new prisoner had been stripped, humiliated, intimidated, showered, and rubbed with the Brer Fox odour, we had our mugshots taken. I was faint from weariness, my hair wet and slicked back behind my ears. This really helped create the look they were after.

These ugly mugshots were printed onto an I.D. tag and given to us to pin to our chest. I pinned mine on back-to-front so no one would see it, but a guard came along and yelled, “Are you an imbecile …?”

I certainly looked like one.

We were told to each take two plastic sacks from the pile. “Take the bags with your initials, for fuck’s sake, and stand in a straight line against the wall.”

“Attention!”

It was our first muster – of sorts. We stood in a row along the wall, our shoulders and arms touching, our faces in sombre shades of ethnicity. There was no one to hug us and tell us it was going to be okay (and they would have been lying, anyway). We were tired, traumatised, scared, aching for our children, and some were very obviously coping with withdrawal – mostly from the drug Ice.

Spinner was having a difficult time standing still.

Annie Oakley looked as if she was in the army.

Macy was sizing up the guards.

Grunter was a lost soul.

Zorba and Nina looked scared.

I didn’t know any of these women, but, as we stood with our back to the wall, staring into the faces of our oppressors, I was no longer convinced I could cope by pretending this was just a journalistic assignment.

Yet, standing between Annie Oakley and Macy, I felt as if I were with my crew. After dreading prison for so long, I was oddly at ease with these two women. Drifting into my imagination, I was presented with a bizarre fantasy: all of us marching through the jungle, Macy leading the way, Annie Oakley barking orders, Spinner stealing aeroplanes, and me … well, after almost two decades as a fugitive living on the edge, I knew a thing or two about keeping out of sight and surviving.

We were led out of reception into the great outdoors, a compound surrounded by high wire enclosures topped with coils of razor wire. Gaudy-coloured buildings. Concrete pavements leading in all directions. The depressing stench of sewage, boiled cabbage, and the body sweat of too many caged humans, together with a noise that could well have been coming from a crowd at a football stadium.

The plucking of Nina from the pack was so quick that she was on her way along another path before we knew she’d been taken. I learned later that she was whisked away to the isolation block (also called the boneyard) for her own safety, something to do with her newborn baby.

Down a path we went, past the desolate Visits Centre, and the clanging kitchen, the medical centre and, across the way, a caged gym, inmates rushing to stare out at us, the new arrivals. There were patches of grass the size of a Cornflakes box along the way, with mocking signs: ‘Do Not Walk on Grass.’

We came to a standstill outside a large building: ‘Secure 7’. ‘Secure 8’.

The magic door swung open.

We were ordered inside and marched along grey-white tiles, up a corridor and around a bend to a heavy door: ‘Secure 8’.

I could hear Macy breathing beside me. I saw the perspiration on Spinner’s top lip. Annie Oakley had gone deathly quiet.

The door swung open.

It looked like a mental asylum. We stared into a crowd of ghoulish prisoners. These morbid creatures sat around metal tables drinking skim milk from 600 ml cartons, milk-lipped, cross-eyed, mouths full of broken and rotting teeth. The fucked-up hair! The weeping sores. Bloodthirsty and drugged to the eyeballs… how the hell long had these women been locked up?

“Come on, mate, move your arse!”

If I’d not been shunted along by Annie Oakley, I might have been rooted to the spot. There was nothing but wretchedness ahead … or so I thought until she stood up. If I had to describe this woman in two words, I’d say “Venus Williams”; she was tall, brown-skinned, stunning, and poised – just like the tennis player.

Her vision narrowed to a pinprick. “Hey, you,” she called. “You can sit with us!”

In hindsight, that was a magic prison moment. Venus had singled me out.

I would later learn that she had been incarcerated nine times since she was a kid. She has a knife-slash scar across her cheek bone, warning us of her past. She can knock a grown man out with a fist hardened by a lifetime of injustice and driven by the pain and anguish she has endured.

Any other woman might have taken her offer like the jewel it was, but I was prison green and knew no better, and, besides, I desperately needed to withdraw into myself. It has been a traumatic week and a metal bench beneath a protective spiral staircase beckoned me.

Sitting down, I stared at the three small cells in front of me. Cages for women. There were more cells behind me and along the back wall, where a hefty drink dispensing machine sparkled with orange, silver and yellow cans. I would soon learn that tokens could be purchased to poke into the coin slot and out would pop a Fanta, Coke, or Lemonade.

“New arrivals. Over here. Now!”

Back I went through the throng of gawking inmates, carefully avoiding the skinny waif who kept bellowing, “Who ate all the fucking jam?”

I stood in a huddle with Annie Oakley, Macy, Spinner, Zorba and Grunter. We paid attention to the female officer who told us the rules: “You will be doubled up in a cell. There is only one bed in each cell, but you will find two mattresses on that bed. One mattress will go on the floor at bedtime.”

During the lead-up to my trial I had read about the over-crowding and horrendous conditions inside this prison. I now began praying: please cell me up with Annie Oakley; please, dear patron saint of prisoners, do not put me with a lunatic; please don’t put me with Zorba the old stripper, or Grunter…

“Choose a cell-mate and …”

We got to choose! I quickly moved closer to Annie Oakley. Surely, she would remember our meat-wagon solidarity… but, no, she slung her arm through Spinner’s – best friends now, both druggies, both rally car drivers. I didn’t stand a chance. I’d lost my first prison friend as soon as I’d met her.

Macy grabbed my arm. “You’re with me,” she said.

Oh, glory, to be penned up with a giant teenager. But had I known what was to come, I would have been praying to be caged with Macy in the first place. We were not given the key to our new pad. No such luck. In fact, we were locked out until it was time to be locked in.

I went back to the bench.

“Hey, you, you fucking cunt.”

Were they talking to me? Venus was surrounded by her cronies, all silent, all sneering at me. One bleached blonde with severely rotted teeth beheld me with a calm, foreboding contemplation, as if visualising my dead body.

Venus clenched her strong jaw, narrowed her captivating dark eyes. “You’re dead.”

I’d been in Secure 8 no more than a half-hour and someone wanted to kill me. Well, not just someone – an entire mob.

By now, what was left of my innards was shrunken with trepidation, a hard walnut-sized knot that sucked the energy out of me. I lay down on the floor outside my assigned prison cell and stared up at the floor above. More cells. It was like a zoo, but once all the women were locked in their cages, I’d feel safe for a while.

And then something unexpected happened. In an act of solidarity, Annie Oakley crossed the floor and lay down beside me. She reached an arm across my shoulders: “What the fuck have you done, mate?”

It was a dangerous act of kindness. My throat froze with a painful knot, my eyes burned with tears. This woman, who seemed so lost in her own troubles, was awake to what was going down and offered me support, at the risk of the mob turning on her.

“Muster up!”

Annie Oakley and I quickly jumped to our feet as the stampede of inmates rushed into the tight alcove surrounding the staircase, to stand outside cell doors. Other inmates thumped up the stairs.

And then … a silence that could have heard a pin drop, as two officers entered. The male officer stood silent as the female officer began reading off names, and we responded. When she’d finished, the pair made their way up the staircase.

Silence prevailed.

I cast my eyes over the faces of the women I’d be living with. Too many of them were looking straight at me. Just a few more minutes and I’d be locked down in my cell with Macy. A few more minutes and I’d have made it through my first day in prison. But just then Venus broke away from the wall and surged forward, her eyes glistening with anger.

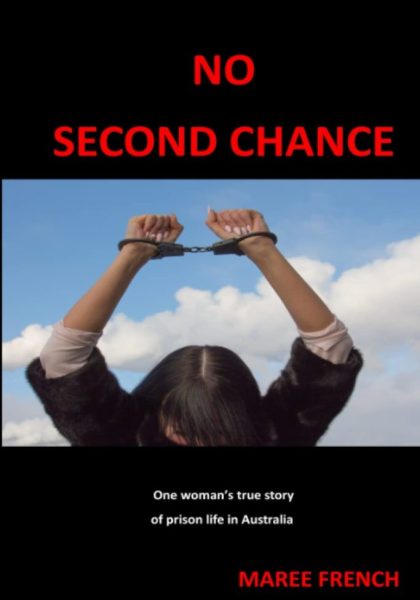

No Second Chance

No Second Chance is Maree French’s first-hand account of life as a female prisoner in the Queensland jail system.

She tells the unvarnished truth about Brisbane Women’s Correctional Centre, an overcrowded hellhole where women were caged together in cells built for one, or in un-policed group units, where violence was the accepted mode of communication…